Revell 1/48 SB2C-3 Helldiver

|

KIT #: |

? |

|

PRICE: |

$29.95 SRP |

|

DECALS: |

Two Options |

|

REVIEWER: |

Tom Cleaver |

|

NOTES: |

'Big Ed' photo etch set |

The Curtiss Helldiver was the most problematic American

naval aircraft to see production and operational use during the Second World

War.

Planned as the replacement of the Douglas SBD Dauntless shipboard dive

bomber, the SB2C promised higher performance in speed, range and payload; in the

end, it failed to meet its designated performance parameters on any of these

points, yet force majeure saw it remain

in production throughout the war (one can consider the SB2C the

great-grandfather of those current boondoggles, the F/A-18 and the F-35B/C,

which have also failed to meet their original performance parameters and have

still been placed into production).

Over 800 separate changes in three major modification

programs were required to get one squadron of SB2C-1 Helldivers onto a carrier

deck over 18 months later than originally expected.

The SB2C-1 was underpowered due to the decision to use

the R-2600 radial engine.

This problem would remain with the design through the

SB2C-1C and the early and mid-production SB2C-3 sub-types, with the late

production SB2C-3 and SB2C-4 utilizing an uprated R-2600 that provided

sufficient power so that every carrier takeoff didn’t feel like a potential

crash to the crew.

Additionally, the poor design of the dive brakes meant

that the airplane was never as accurate a dive bomber as the airplane it

replaced, the SBD, until the late production SB2C-3 and the subsequent SB2C-4

were given perforated dive flaps along the line of those originally utiized by

the SBD.

The later versions of the SB2C-3, which first arrived in

fleet squadrons in the summer of 1944, and the SB2C-4 that appeared on

operations shortly after the battle of Leyte Gulf, were the Helldiver the Navy

had originally hoped for in terms of performance and reliability.

Their careers aboard the fast carriers were shortened by

the fact the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair could carry the same bomb load as the

SB2C, and could easily revert to their fighter role; this became crucial with

the appearance of the Kamikaze.

By the time of the

Okinawa

campaign, most fast carriers had completely replaced SB2Cs with the F6F and F4U

in the fighter-bomber role.

John D. Bridgers - Helldiver Pilot:

War arrived for America on Sunday, December 7, 1941. InGreenville, North Carolina, recently-commissioned Ensign John

D. Bridgers was home on leave awaiting orders to a fleet

squadron, having just graduated as a Naval Aviator after

joining the Navy’s Aviation Cadet program in February, 1941. A 1940 graduate of East Carolina Teacher’s College, Bridgers

had hoped to go on to medical school. However, he knew he had

to go to work since his family was still dealing with the

aftereffects of the Depression. As he recalled, “In North

Carolina, a beginning teacher received a monthly salary of

$96.50. From this salary one was expected to house, clothe

and feed one’s self as well as suffer pension withholdings and

pay taxes. While contemplating that, I learned I could make

$105.00 per month in the Navy as an Aviation Cadet with board,

lodging and clothing furnished. In a year, if successful in

flight training, I would be commissioned an Ensign in the

Naval Reserve with a $250.00 per month salary, again with

lodging provided and an allowance for food, and with a half-month’s bonus for flight pay. Further, for foregoing four

formative years one typically spent on temporary employment,

the reserve aviator would receive $1000.00 per year bonus at

discharge - $4,000. To a son of the Depression, these seemed

princely arrangements, and the flight bonus would provide a

nest egg if I needed more college before medical school.”

War arrived for America on Sunday, December 7, 1941. InGreenville, North Carolina, recently-commissioned Ensign John

D. Bridgers was home on leave awaiting orders to a fleet

squadron, having just graduated as a Naval Aviator after

joining the Navy’s Aviation Cadet program in February, 1941. A 1940 graduate of East Carolina Teacher’s College, Bridgers

had hoped to go on to medical school. However, he knew he had

to go to work since his family was still dealing with the

aftereffects of the Depression. As he recalled, “In North

Carolina, a beginning teacher received a monthly salary of

$96.50. From this salary one was expected to house, clothe

and feed one’s self as well as suffer pension withholdings and

pay taxes. While contemplating that, I learned I could make

$105.00 per month in the Navy as an Aviation Cadet with board,

lodging and clothing furnished. In a year, if successful in

flight training, I would be commissioned an Ensign in the

Naval Reserve with a $250.00 per month salary, again with

lodging provided and an allowance for food, and with a half-month’s bonus for flight pay. Further, for foregoing four

formative years one typically spent on temporary employment,

the reserve aviator would receive $1000.00 per year bonus at

discharge - $4,000. To a son of the Depression, these seemed

princely arrangements, and the flight bonus would provide a

nest egg if I needed more college before medical school.”

The week after Pearl Harbor, Bridgers found his expected

assignment to the Atlantic Fleet had been changed when he

received orders sending him to Pearl Harbor to join Bombing

Squadron Three at the Ford Island Naval Air Station. After

traveling to San Francisco by train just before Christmas,

Bridgers went aboard the SS President Hoover along with 2,000

construction workers, headed for Pearl Harbor. His group of

Naval Aviators found themselves bunking in what had been the

ship’s cocktail lounge. After a week at sea, they sighted

Diamond Head. “As we pulled into Pearl Harbor, I recalled

having seen a newsreel by the Secretary of the Navy, Frank

Knox, maintaining that little substantial damage had been done

to the Pacific Fleet by the Pearl Harbor attack. We looked

out and saw that the waters were still uniformly oil-covered;

we passed the still-grounded battleship USS Nevada in the

channel. In the harbor itself were more derelicts including

the capsized U.S.S. Oklahoma, the sunken USS West Virginia,

and the remains of the blasted USS Arizona. It was evident

there had been grievous hurt inflicted by the enemy. I made a

promise to myself as I viewed this destruction that I would

repay the investment the Navy had made in me one day by doing

something to avenge this.”

Bombing-Three had been left behind in Hawaii when USS

Saratoga returned to the west coast for repairs after being

torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in late December, 1941. New

naval aviators were assigned to the unit to complete their

advanced training, and it was here that Bridgers made the

acquaintance of the SBD Dauntless. After six weeks’ training,

the unit was sent aboard USS Enterprise for a special mission.

Bridgers, who had yet to qualify as a carrier pilot, was

surprised to find himself included. At sea a day later, they

made rendezvous with USS Hornet, which presented a strange

sight with sixteen Army bombers tied down on her flight deck.

Bridgers’ introduction to war was to participate in the

Doolittle Raid. As the ships headed back to Hawaii after

launching the raiders, Ensign Bridgers was able to make the

three carrier landings that qualified him fully as a Naval

Aviator.

Upon return from this mission, Bombing Three had ten days

before they were alerted they would go aboard USS Yorktown for

a mission of utmost importance upon her arrival back in Pearl

Harbor from the Battle of the Coral Sea. The pilots were

awestruck when they saw the condition of the badly-damaged

Yorktown, which set out to sea after three days in port with

construction workers still aboard making her fit to see

combat. Bridgers’ participation in the Battle of Midway was

limited to searches flown on the way out; he and other

inexperienced young pilots were held in reserve on June 4. Later that day, he survived the two Japanese air attacks on

Yorktown. When the ship was torpedoed and sunk by I-26,

Bridgers was among the survivors picked up by escorting

destroyers.

Within a week of his return to Hawaii, Ensign Bridgers

was assigned to Scouting Six, which went aboard the newly-returned Saratoga; after two more weeks of training, the ship

was underway for the South Pacific. Bridgers flew his first

combat mission on August 7, 1942, providing air support for

the invasion of Guadalcanal. For the next three months he was

intimately involved with that fateful struggle, participating

in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, and later being among

the pilots sent to the island

itself following Saratoga’s

second torpedoing. Newly promoted to Lieutenant (j.g.),

Bridgers went back aboard Saratoga with Scouting Six now

redesignated Bombing Thirteen, and participated in the central

Solomons campaign in early 1943, when Saratoga operated in

concert with HMS Victorious.

itself following Saratoga’s

second torpedoing. Newly promoted to Lieutenant (j.g.),

Bridgers went back aboard Saratoga with Scouting Six now

redesignated Bombing Thirteen, and participated in the central

Solomons campaign in early 1943, when Saratoga operated in

concert with HMS Victorious.

In June, 1943, then-Lieutenant Bridgers was separated

from Bombing Thirteen and returned to San Francisco aboard

Victorious. After a month’s leave, he received his new orders

to report to Norfolk Naval Station to commission a new

squadron, Bombing-Fifteen. Here, Bridgers and two of his

fellow Saratoga veterans formed a core of experience deeply

appreciated by squadron commander Lieutenant Commander James

Mini, and Bridgers became Squadron Engineering Officer. At

first, the unit flew the SBD Dauntless, but in early November,

the first of their new SB2C-1C Helldivers arrived. As

Engineering Officer, Bridgers was at the forefront of the

struggle to get the new airplane operational. “I was to come

to know well the mechanical intricacies of The Beast, and

particularly appreciated the aphorism that the SB2C had three

less engines and one more hydraulic fitting than the B-17."

By January 1944 Bombing-Fifteen, along with Fighting-Fifteen

and Torpedo-Fifteen, were ready to go aboard their carrier,

the new USS Hornet.

Along with the rest of Air Group Fifteen, Bridgers ran

into the “hornet’s nest” that was Hornet’s captain, Miles

Browning. The Air Group was put ashore in Hawaii, excoriated

by Browning as being unready for combat. The Air Group

Commander was replaced by the commander of Fighting-Fifteen,

LCDR David McCampbell. Bridgers particularly missed the 36

SB2C-1Cs they had left aboard Hornet, which he had been responsible for working on so they were finally combat-ready.

After a six week marathon of training, during which Bridgers

and the engineering section worked every minute not spent

flying to make another 36 Helldivers combat-ready, the air

group passed their Operational Readiness Inspection and went

aboard USS Essex at the end of April, 1944. They departed for

the Western Pacific on May 3. Bridgers was leader of the

second division of Bombing Fifteen, which the members named

“The Silent Second.”

A month later, he and the rest of the squadron flew their

first big mission against the airfields on Saipan as part of

the invasion of the Marianas. Fortunately for Bombing-Fifteen, Task Group 58.4 was too far to the east to take part

in the strikes against the Japanese fleet in the “Mission

Beyond Darkness” that saw half the fleet’s Helldivers that

participated lost due to running out of fuel on the return

flight to the fleet. Bombing Fifteen spent the next six weeks

providing support for the invasions of Tinian and Guam with

two side trips back to Eniwetok to replenish supplies and

replace shot-up aircraft.

On August 26, 1944, Essex arrived at Eniwetok to

replenish. Bombing Fifteen was re-equipped with mid/late SB2C-3 Helldivers. These were distinguished from the previous

SB2C-3s that had equipped the squadron by their 4-bladed prop,

and an additional 250 horsepower. Bridgers recorded that the

new Helldiver made takeoffs far less “adventurous” than they

had been in the earlier models. Bombing Fifteen was reduced

from 36 aircraft to 26, while ten pilots were moved to

Fighting Fifteen to fly additional Hellcats added to the

squadron.

Air Group Fifteen next provided support for the Marines

in the invasion of Peleliu. This was followed by operations

across the central and northern Philippines. The most

spectacular single mission for Air Group Fifteen happened off

the east coast of Luzon, when an enemy convoy of 42 ships was

sighted. The Helldivers and Avengers sank 18, left five

burning fiercely, nine dead in the water and trailing oil,

seven hit, and three damaged but under way; several ammunition

ships made spectacular sights when hit. Overall, the

Philippines strikes by Task Force 38 - combined with the

strikes on Okinawa and Formosa that denied reinforcements to

the Philippines - were so successful that the invasion

schedule for Leyte was moved up to October 20, 1944.

Air Group Fifteen next provided support for the Marines

in the invasion of Peleliu. This was followed by operations

across the central and northern Philippines. The most

spectacular single mission for Air Group Fifteen happened off

the east coast of Luzon, when an enemy convoy of 42 ships was

sighted. The Helldivers and Avengers sank 18, left five

burning fiercely, nine dead in the water and trailing oil,

seven hit, and three damaged but under way; several ammunition

ships made spectacular sights when hit. Overall, the

Philippines strikes by Task Force 38 - combined with the

strikes on Okinawa and Formosa that denied reinforcements to

the Philippines - were so successful that the invasion

schedule for Leyte was moved up to October 20, 1944.

The Japanese responded to the Leyte invasion with all of

their available fleet. On October 24, 1944, the strongest

Japanese surface fleet to ever put to sea was spotted in the

Sibuyan Sea, headed toward San Bernardino Strait and the

invasion forces in Leyte Gulf. By now promoted to Lieutenant

Commander, Bridgers took part in the strikes against the

Japanese Fleet. The attack by Bombing Fifteen and Torpedo

Fifteen against the Japanese battleship Musashi was later

judged to have resulted in the major bomb and torpedo hits

that led to her sinking later that evening. In two missions

against the Center Force, Bombing Fifteen hit Musashi with ten

bombs and the battleship Nagato with three.

Late that afternoon, search planes finally found the

Japanese carriers Halsey was seeking, not knowing that the

four carriers located off Luzon’s Cape Engano were there as

bait to bring Halsey away from the invasion forces and open

them to attack by Admiral Kurita’s center force that had been

attacked the day before. That night, Halsey took no notice of

a report sighting the Center Force moving through San

Bernardino Strait, and three task groups of Task Force 38

headed north to get the Japanese carriers.

October 25, 1944, found Bridgers at the head of the Essex

strike force headed for the Japanese fleet, CDR Mini having

been shot up the day before over the Japanese Center Force and

forced to ditch near a US destroyer.

Arriving overhead, he looked down and recognized the

Japanese carrier Zuikaku, the last survivor of the six

carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor nearly three years

earlier. The Essex strike was so successful, the bombers were

given full credit for the sinking of Zuikaku, as they made

eight direct hits on the ship. In a mission later that

afternoon they sank the light carrier Chitose with six more

hits. In these attacks, Bombing Fifteen sent 71 sorties that

scored 30 direct hits on Japanese warships, the best record of

any mission flown by any Navy bombing squadron. Bridgers was

awarded the Navy Cross for his efforts in this action.

After Leyte Gulf, Air Group Fifteen was scheduled to

return to the United States, but two different attempts to

leave were scuttled as they were needed in combat over the

Philippines, which involved several strikes against Manila and

strikes against light Japanese naval forces in the centralPhilippines. When the air group was finally relieved in late

November, Bombing Fifteen had only 14 Helldivers left aboard.

After Leyte Gulf, Air Group Fifteen was scheduled to

return to the United States, but two different attempts to

leave were scuttled as they were needed in combat over the

Philippines, which involved several strikes against Manila and

strikes against light Japanese naval forces in the centralPhilippines. When the air group was finally relieved in late

November, Bombing Fifteen had only 14 Helldivers left aboard.

Between May and November, 1944, Bombing Fifteen and

Torpedo Fifteen sank 37 cargo vessels, probably sank 10 more,

and damaged 39, for a total score of 174,300 tons of merchant

shipping definitely sunk. Additionally, Musashi, the world’s

largest battleship was sunk, along with Zuikaku, the last

surviving carrier that participated in the Pearl Harbor

attack, one light aircraft carrier, one destroyer, one

destroyer escort, two minesweepers, five escort ships, and two

motor torpedo boats. Of 36 pilots originally assigned to

Bombing Fifteen, twelve were killed during the tour. Air

Group Fifteen’s record was unmatched by any other naval air

group in the war.

After the war, John Bridgers returned home and went to

medical school on the G.I. Bill. In 1951, he took an

assignment as a Naval Aviation flight surgeon, and saw duty

with Task Force 77 off Korea. He returned to his civilian

career in 1955; he was instrumental in the establishment of

the East Carolina University Medical School; he retired from

private practice in 1984 and joined The Joint Commission for

the Accreditation of Hospitals, with which he traveled

nationwide. Following the death of his wife, he eventually

retired to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where he died in May 2007.

The Monogram/Pro-Modeler SB2C-4 was first released in

1997.

It was re-released by Accurate Miniatures as a not very accurate SB2C-1

which I REVIEWED HERE.

This release by Revell is the first re-rel ease

of the original SB2C-4 kit in several years.

Eduard made a very good photoetch set for the SB2C-4

including the complete set of perforated dive brakes that I reviewed earlier.

The kit is very accurate and one of the best kits

Monogram ever made.

ease

of the original SB2C-4 kit in several years.

Eduard made a very good photoetch set for the SB2C-4

including the complete set of perforated dive brakes that I reviewed earlier.

The kit is very accurate and one of the best kits

Monogram ever made.

As I mentioned in my earlier SB2C-4 review, the Eduard

“Big Ed” set will effectively turn your $29.95 kit into a $100 kit, but if you

want a “definitive” Helldiver, it is worth the price, since it provides all the

detail you could want in to cockpits and bomb bay, not to mention the ability to

display the dive brakes right.

I used the Big Ed set for the SB2C-1 which had the

non-perforated dive brakes; these are perfect for doing an SB2C-3 prior to the

very last production batch that introduced the perforated dive brakes.

As far as choosing to do this, remember that in this

crazy hobby “one man’s insanity is another’s seriousness of purpose.”

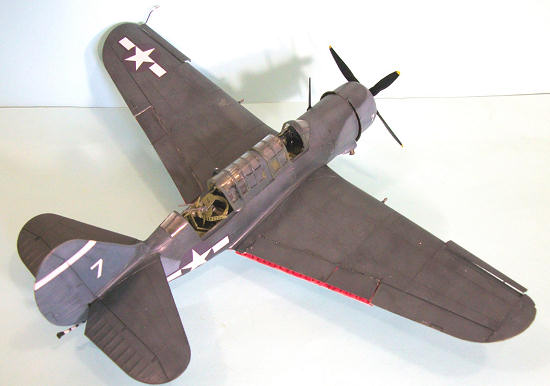

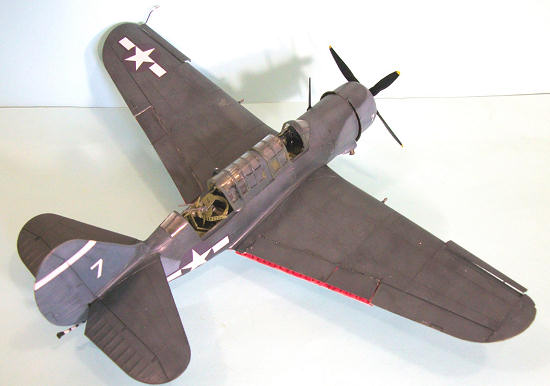

I decided I would do a mid/late production SB2C-3,

having done the SB2C-1, SB2C-1C, SB2C-4 and SB2C-5 over the years.

The mid/late SB2C-3 can have either the unperforated

dive brakes of the earlier sub-types or the later perforated type provided

in the kit, and the engine and 4-bladed prop of the later SB2C-4.

While earlier SB2C-3s have a window on either side

immediately aft of the pilot’s sliding canopy, the mid/late production

version is the first to get rid of that feature.

Thus, this is an easy conversion with a modeler only

needing to modify the propeller hub by extending it about 1/8 inch.

I had the Eduard Big-Ed set to correct the Accurate

Miniatures SB2C-1 release of this kit, which allowed me to do the

unperforated dive brakes and open them up, which

adds

interest to the final look of the model.

I also used the interior upgrade set for the

instrument panel and the other panel faces and radio faces, as well as

additional detail for the rear gun turret.

adds

interest to the final look of the model.

I also used the interior upgrade set for the

instrument panel and the other panel faces and radio faces, as well as

additional detail for the rear gun turret.

I cut off the dive brake interior detail from the

plastic wing parts before assembling the wings. The best way to attach the wings

for this model is to glue them to the fuselage halves prior to further assembly

of the fuselage.

This allows you to work that joint from inside and out, and get

it nice and tight without having to worry about filling any seams.

I decided to close the bomb bay on this model, which

involved cutting the bomb bay doors off the interior wall parts, and then gluing

them in position on each fuselage half. I reinforced this with Evergreen strip

along the inside of the door.

The cockpit interior parts were painted Interior Green

and assembled, with various parts replaced with the Eduard photoetched parts.

I also assembled the gun turret and set it aside.

With the interior installed, I glued the fuselage halves

together and attached the horizontal stabilizers.

Eduard’s set included masks for the extensive canopies,

which made painting them easier.

I painted the interior of the photoetch dive brakes

Tamiya Flat Red, with the exterior done in the tri-color camouflage.

After pre-shading the model, the lower surfaces were

painted with Tamiya Flat White.

The outer undersides of the wings and the fuselage sides

and vertical fin were painted with Gunze-Sangyo Intermediate Blue, while the

upper surfaces were painted

with a mix

of Tamiya Sea Blue and Field Blue.

All of these upper colors were post-shaded to simulate

sun-fading as would be experienced in the Central Pacific.

with a mix

of Tamiya Sea Blue and Field Blue.

All of these upper colors were post-shaded to simulate

sun-fading as would be experienced in the Central Pacific.

I used decals out of the decal dungeon for the national

insignia and plane-in-group number.

The kit decals were used for the very small stencils.

I did exhaust and oil stains with Tamiya Smoke, then

gave the model several coats of Xtracrylix Flat Varnish, with some Tamiya Flat

Base mixed in to get a very flat sun-faded finish.

I unmasked the canopies and put them in position after

fitting the gun turret in the rear cockpit, then finished off by attaching the

prop, landing gear and radar antennas.

The Beast may not have been a very good dive bomber, but

it has always been an interesting-looking airplane, and Monogram’s kit catches

its lines very well indeed.

No collection of US Navy Second World War carrier

aircraft is complete without two or three done as the differing versions. I have

now completed two of the three Air Group 15 models I plan to do.

The Beast may not have been a very good dive bomber, but

it has always been an interesting-looking airplane, and Monogram’s kit catches

its lines very well indeed.

No collection of US Navy Second World War carrier

aircraft is complete without two or three done as the differing versions. I have

now completed two of the three Air Group 15 models I plan to do.

With thanks to Commander Bridgers for writing one of the best personal

memoirs of World War II naval air combat, “The Naval Years,” which you can read

here:

http://tk‑jk.net/Bridgers/Mainpages/NavalYears.html

Tom

Cleaver

February 2012

Copyright ModelingMadness.com. All rights reserved. No reproduction in any form without express permission from the editor.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the

Note to

Contributors.

Back to the Main Page

Back to the Previews Index Page2025

War arrived for America on Sunday, December 7, 1941. InGreenville, North Carolina, recently-commissioned Ensign John

D. Bridgers was home on leave awaiting orders to a fleet

squadron, having just graduated as a Naval Aviator after

joining the Navy’s Aviation Cadet program in February, 1941. A 1940 graduate of East Carolina Teacher’s College, Bridgers

had hoped to go on to medical school. However, he knew he had

to go to work since his family was still dealing with the

aftereffects of the Depression. As he recalled, “In North

Carolina, a beginning teacher received a monthly salary of

$96.50. From this salary one was expected to house, clothe

and feed one’s self as well as suffer pension withholdings and

pay taxes. While contemplating that, I learned I could make

$105.00 per month in the Navy as an Aviation Cadet with board,

lodging and clothing furnished. In a year, if successful in

flight training, I would be commissioned an Ensign in the

Naval Reserve with a $250.00 per month salary, again with

lodging provided and an allowance for food, and with a half-month’s bonus for flight pay. Further, for foregoing four

formative years one typically spent on temporary employment,

the reserve aviator would receive $1000.00 per year bonus at

discharge - $4,000. To a son of the Depression, these seemed

princely arrangements, and the flight bonus would provide a

nest egg if I needed more college before medical school.”

War arrived for America on Sunday, December 7, 1941. InGreenville, North Carolina, recently-commissioned Ensign John

D. Bridgers was home on leave awaiting orders to a fleet

squadron, having just graduated as a Naval Aviator after

joining the Navy’s Aviation Cadet program in February, 1941. A 1940 graduate of East Carolina Teacher’s College, Bridgers

had hoped to go on to medical school. However, he knew he had

to go to work since his family was still dealing with the

aftereffects of the Depression. As he recalled, “In North

Carolina, a beginning teacher received a monthly salary of

$96.50. From this salary one was expected to house, clothe

and feed one’s self as well as suffer pension withholdings and

pay taxes. While contemplating that, I learned I could make

$105.00 per month in the Navy as an Aviation Cadet with board,

lodging and clothing furnished. In a year, if successful in

flight training, I would be commissioned an Ensign in the

Naval Reserve with a $250.00 per month salary, again with

lodging provided and an allowance for food, and with a half-month’s bonus for flight pay. Further, for foregoing four

formative years one typically spent on temporary employment,

the reserve aviator would receive $1000.00 per year bonus at

discharge - $4,000. To a son of the Depression, these seemed

princely arrangements, and the flight bonus would provide a

nest egg if I needed more college before medical school.”  itself following Saratoga’s

second torpedoing. Newly promoted to Lieutenant (j.g.),

Bridgers went back aboard Saratoga with Scouting Six now

redesignated Bombing Thirteen, and participated in the central

Solomons campaign in early 1943, when Saratoga operated in

concert with HMS Victorious.

itself following Saratoga’s

second torpedoing. Newly promoted to Lieutenant (j.g.),

Bridgers went back aboard Saratoga with Scouting Six now

redesignated Bombing Thirteen, and participated in the central

Solomons campaign in early 1943, when Saratoga operated in

concert with HMS Victorious.  Air Group Fifteen next provided support for the Marines

in the invasion of Peleliu. This was followed by operations

across the central and northern Philippines. The most

spectacular single mission for Air Group Fifteen happened off

the east coast of Luzon, when an enemy convoy of 42 ships was

sighted. The Helldivers and Avengers sank 18, left five

burning fiercely, nine dead in the water and trailing oil,

seven hit, and three damaged but under way; several ammunition

ships made spectacular sights when hit. Overall, the

Philippines strikes by Task Force 38 - combined with the

strikes on Okinawa and Formosa that denied reinforcements to

the Philippines - were so successful that the invasion

schedule for Leyte was moved up to October 20, 1944.

Air Group Fifteen next provided support for the Marines

in the invasion of Peleliu. This was followed by operations

across the central and northern Philippines. The most

spectacular single mission for Air Group Fifteen happened off

the east coast of Luzon, when an enemy convoy of 42 ships was

sighted. The Helldivers and Avengers sank 18, left five

burning fiercely, nine dead in the water and trailing oil,

seven hit, and three damaged but under way; several ammunition

ships made spectacular sights when hit. Overall, the

Philippines strikes by Task Force 38 - combined with the

strikes on Okinawa and Formosa that denied reinforcements to

the Philippines - were so successful that the invasion

schedule for Leyte was moved up to October 20, 1944. After Leyte Gulf, Air Group Fifteen was scheduled to

return to the United States, but two different attempts to

leave were scuttled as they were needed in combat over the

Philippines, which involved several strikes against Manila and

strikes against light Japanese naval forces in the centralPhilippines. When the air group was finally relieved in late

November, Bombing Fifteen had only 14 Helldivers left aboard.

After Leyte Gulf, Air Group Fifteen was scheduled to

return to the United States, but two different attempts to

leave were scuttled as they were needed in combat over the

Philippines, which involved several strikes against Manila and

strikes against light Japanese naval forces in the centralPhilippines. When the air group was finally relieved in late

November, Bombing Fifteen had only 14 Helldivers left aboard.  ease

of the original SB2C-4 kit in several years.

Eduard made a very good photoetch set for the SB2C-4

including the complete set of perforated dive brakes that I reviewed earlier.

The kit is very accurate and one of the best kits

Monogram ever made.

ease

of the original SB2C-4 kit in several years.

Eduard made a very good photoetch set for the SB2C-4

including the complete set of perforated dive brakes that I reviewed earlier.

The kit is very accurate and one of the best kits

Monogram ever made. adds

interest to the final look of the model.

I also used the interior upgrade set for the

instrument panel and the other panel faces and radio faces, as well as

additional detail for the rear gun turret.

adds

interest to the final look of the model.

I also used the interior upgrade set for the

instrument panel and the other panel faces and radio faces, as well as

additional detail for the rear gun turret. with a mix

of Tamiya Sea Blue and Field Blue.

All of these upper colors were post-shaded to simulate

sun-fading as would be experienced in the Central Pacific.

with a mix

of Tamiya Sea Blue and Field Blue.

All of these upper colors were post-shaded to simulate

sun-fading as would be experienced in the Central Pacific. The Beast may not have been a very good dive bomber, but

it has always been an interesting-looking airplane, and Monogram’s kit catches

its lines very well indeed.

No collection of US Navy Second World War carrier

aircraft is complete without two or three done as the differing versions. I have

now completed two of the three Air Group 15 models I plan to do.

The Beast may not have been a very good dive bomber, but

it has always been an interesting-looking airplane, and Monogram’s kit catches

its lines very well indeed.

No collection of US Navy Second World War carrier

aircraft is complete without two or three done as the differing versions. I have

now completed two of the three Air Group 15 models I plan to do.