|

KIT: |

Trumpeter 1/32 P-40B Tomahawk |

|

KIT # |

? |

|

PRICE: |

$49.95 MSRP |

|

DECALS: |

Two options |

|

REVIEWER: |

Tom Cleaver |

|

NOTES: |

|

HISTORY |

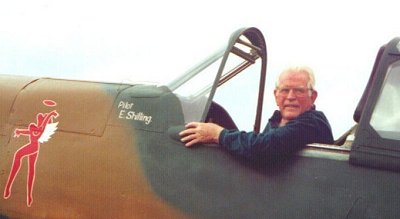

Erik Shilling - The Tiger’s Tiger:

It was hot on Don Muang Airport outside Bangkok on December 10, 1941, as the humidity increased with the rising tropic sun. The crews of the 60th, 62nd and 98th Sentais sweated to ready the 48 Mitsubishi Ki.21 Type 97 bombers (later to be known to their Allied opponents as the Sally) to support the coming offensive against Burma. Had any of them looked up as they paused to wipe sweat, they likely wouldn't have seen the small dot high overhead and - if they had - they wouldn't have seen it as the threat it was.

Flying at 26,000 feet, where the Allison engine of his Curtiss H-87A-2 "Tomahawk" made a sound inaudible to those on the ground, Flying Officer Erik Shilling of the American Volunteer Group tripped the wire leading to the camera in the baggage compartment behind him, and began photographing the docks and surrounding airfields below. Having been involved in Army Air Corps long-range photo reconnaissance experiments before joining the AVG, Shilling had convinced AVG Commander Claire Chennault to modify his airplane with a Fairchild camera to give the AVG such photo recon capability.

Shilling’s

mission to photograph Bangkok was the first offensive operation

undertaken by Americans in the Pacific War, 48 hours after news of the

attack on Pearl Harbor had flashed around the world.

Shilling’s

mission to photograph Bangkok was the first offensive operation

undertaken by Americans in the Pacific War, 48 hours after news of the

attack on Pearl Harbor had flashed around the world.

Off to the west of the city, AVG Group Intelligence Officer Allen Christman and future ace Ed Rector circled, awaiting Shilling's rendezvous. The three Americans had left their base at Toungoo north of Rangoon before dawn, dropping in at the British base of Mingaladon outside Rangoon at first light to refuel, pausing one last time to top off at Tavoy on the Burmese-Thai border, so they could make the flight all the way to Bangkok and return directly to Toungoo. The Japanese had word of the mission - twenty minutes after the trio left Tavoy, Japanese fighters attacked the field, strafing everything in sight.

Rector saw the approaching dot in the distance resolve itself as Shilling's plane. As the three headed home, Shilling had photos revealing 90 Japanese aircraft - 50 bombers and 40 fighters - ready to strike Rangoon. 57 years later, the United States Government would officially recognize the AVG as members of the American armed forces; at age 80, Erik Shilling was awarded the U.S. military Silver Star for this important mission.

The son of a World War I pilot, Erik Shilling joined the Air Corps in 1938. By early 1941, with several hundred hours in the P-36, and time in the new P-40, he was reading newspaper reports of the Japanese assault on China. "It was apparent to anyone who paid attention that the war wasn't going to be just limited to Europe. Like it or not, we in America were going to become involved, and it was going to spread to Asia."

That April, President Roosevelt signed an unpublicized executive order authorizing recruitment of enlisted men and reserve officers on duty with the U.S. armed forces, and the British released 100 Lend-Lease Curtiss H-87-A2 "Tomahawks" for transfer to China. With U.S.-Japanese relations in a delicate position, the recruiting officers for the American Volunteer Group had to offer contracts that were "legally consistent" with official U.S. policy. While the operation had the blessing of the government, it was ostensibly organized by the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO), run by Edward D. Pawley, who was later described by Life magazine as "always able to be at the right place a few minutes before the right time." The contracts made no mention of the true nature of their service, stating that the signatories were hired to "manufacture, repair and operate aircraft."

The original

plan included three groups of volunteers: two fighter groups and one

bomber group. The first group would be equipped with Curtiss P‑40s, while

the next would have Seversky P‑43s; the third - a bombardment group - was

to be equipped with, Lockheed Hudsons. The Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor forced the cancellation of the second and third groups.

The original

plan included three groups of volunteers: two fighter groups and one

bomber group. The first group would be equipped with Curtiss P‑40s, while

the next would have Seversky P‑43s; the third - a bombardment group - was

to be equipped with, Lockheed Hudsons. The Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor forced the cancellation of the second and third groups.

"In fact," Shilling told me in February 2002, a month before he passed on, "we were an official undercover operation of the American government. We were not mercenaries, though that cover story was so good everyone has believed it for the past sixty years." Shilling buttressed his statement by pointing out that when the American Volunteer Group traveled to China aboard the Dutch passenger ship S.S. Jagersfontein, "we were escorted by two U.S. Navy heavy cruisers - the USS Salt Lake City and the USS Northampton - because there was a real fear that the Japanese had heard about the operation and would attempt to intercept us." The cruisers stayed with them all the way across the Pacific, until the Jagersfontein entered the Java Sea and headed for Singapore.

In later years, many would believe that the American Volunteer Group (they received their popular name of “Flying Tigers” in news reports of their combat over Rangoon on Christmas Day, 1941) had fought in China against the Japanese for years before the attack on Pearl Harbor. In truth, the A.V.G. did not arrive in Burma until late July 1941, and did not reach their first base at Tongou, in central Burma, until early August. Their first operational mission was not flown until December 10, 1941, after Pearl Harbor; their first combat mission - intercepting the first raid by the Japanese Army Air Force against Rangoon - came on December 23, 1941.

During training that fall of 1941, three squadrons were organized: the "Adam and Eves" (the first pursuit), the "Pandas," and the "Hells Angels." A member of the third squadron, Erik Shilling ended up creating the insignia that would forever be linked with the Flying Tigers. "It's always been said that the tiger mouth came about after we saw a picture of a P-40 being flown by 112 Squadron in North Africa," Shilling told me in his final interview. "That's not true. I was looking through a British magazine one day and saw a photo of a Me-110 with a shark face on it. They were from the 'Haifisch Gruppe.' I thought it looked perfect for our squadron insignia." Shilling chalked a sharkmouth on his P-40 to see how it might look; when he asked Chennault for permission to use it as a squadron marking, Chennault saw it as the group marking. Shilling ended up chalking the sharkmouth on all of the P-40s at Tongou before they were painted. "That's why there were no two of them with the same mouth."

After the

Bangkok recon mission, Shilling's adventures were far from over. He flew

numerous solo reconnaissance missions over Burma, Thailand and Northern

French Indochina, almost always unescorted. In late January 1942, he led

a flight of three in Curtiss-Wright CW-21 "Demons" on a flight from

Chungking to Kunming. In heavy weather, he suffered engine failure and

crashed in the mountainous jungle of southeastern China, while one of the

others flew into a mountainside and was killed.

After the

Bangkok recon mission, Shilling's adventures were far from over. He flew

numerous solo reconnaissance missions over Burma, Thailand and Northern

French Indochina, almost always unescorted. In late January 1942, he led

a flight of three in Curtiss-Wright CW-21 "Demons" on a flight from

Chungking to Kunming. In heavy weather, he suffered engine failure and

crashed in the mountainous jungle of southeastern China, while one of the

others flew into a mountainside and was killed.

As Shilling climbed out of the wreck, he was surrounded by tribal villagers who had seen the crash. "I'm an American!" he exclaimed. It meant nothing to these people, who in the middle of the 20th Century were unaware there were Europeans. All they knew was that their country was at war with the Japanese, who flew in metal birds, and that this man who flew a metal bird was not like them. So far as they were concerned, this was proof he was Japanese and they treated him accordingly. Shilling was imprisoned in a hole, from which it was made clear to him he would not leave alive. His luck held when a Chinese Army patrol happened along a few days later before his captors could take action. "The boys in Kunming were very surprised when the Chinese brought me in," he recalled. "They'd already listed me as dead." It was Shilling's experience that prompted the AVG to sew the famous "blood chit" on the back of their flight jackets - it was in effect a branding to insure that indigenous people in the remote areas over which they flew and fought would know an American when they found one, and that they would be well-rewarded for helping him.

In March, 1942, Shilling was chosen to lead six other pilots on a transcontinental mission to obtain new airplanes. After flying across the Himalayas to India, their two week trip involved a flight by Sunderland to what is now Iraq, then across to Palestine, and down to Egypt, where they continued across Africa to Accra in Ghana to pick up six ex-USAAF P-40Es. The return flight took ten days. As Shilling recalled, “We took off early in the morning, so the engines wouldn’t overheat, flew as far as we could, then waited till the next dawn.” The airplanes arrived just in time to stop the final Japanese offensive across the Salween River in early April 1942; had they been successful, Kunming would have fallen, and perhaps Chungking - knocking China out of the war.

In May 1942,

the great battles with the JAAF ended as the monsoon arrived. That June,

rumors abounded regarding their transfer to the USAAF. Unfortunately,

Col. Clayton Bissell - an old enemy of Chennault - was in charge of the

transfer. "That man was perhaps the most incompetent American Army

officer I ever met in my entire life," Shilling said. The meeting was a

disaster. "After

he left, a couple of the guys taught this Chinese kid in the ground crew

that met incoming aircraft to say 'Piss on Bissell.' They told him it was

a greeting he should say to any American when they arrived." The end

came on July 4, 1942, when the AVG was deactivated and the 23rd Fighter

Group was born in its place.

disaster. "After

he left, a couple of the guys taught this Chinese kid in the ground crew

that met incoming aircraft to say 'Piss on Bissell.' They told him it was

a greeting he should say to any American when they arrived." The end

came on July 4, 1942, when the AVG was deactivated and the 23rd Fighter

Group was born in its place.

As one of those who refused induction into the USAAF and then did not return to the United States, Shilling went on to fly C-47s for the Chinese national airline, Civil Air Transport. Between the summer of 1942 and the end of the war, he "flew the hump" - the dangerous cargo-hauling missions from Assam, India, to Chungking, China, over the towering Himalaya mountains - a record 700 times. "The weather over the Himalayas seemed to be permanently bad," he recalled, "and the mountains were so high you could only fly through them with the equipment we had." Flying the Hump was so dangerous, it was later determined that one crew in five crashed during the war, most never to be found. As if the mountains and weather were not enough, there was also the Japanese. "We spotted Jap fighters a few times. The best you could do was to go lower into the mountains, since the turbulence could be so bad it would make them crash if they were stupid enough to follow you." Shilling outflew Japanese fighters while piloting a C-47 through the Himalayas on four occasions, once after being hit by enemy gunfire that had set one engine aflame.

After the end of the war, Shilling remained in the Far East and flew in the Chinese Civil War until the Nationalist retreat to Formosa in 1949. An original member of what would later be known as Air America, in 1951 he flew a C-54 in a resupply mission for Chinese Nationalist Guerillas from Clark Field in the Philippines to Kadena air base on Okinawa - via Chungking, China! - making the flight over the Chinese mainland in daylight in the unarmed transport at an altitude of 500 feet!

Erik also

participated in the resupply missions for the French Army at Dien Bien

Phu, diving his C-82 Packet through heavy anti-aircraft fire from an

entry altitude of 4,000 feet to a drop altitude of 1,200 feet - leveling

off just above stalling speed - to make precision air drops on 45

missions.

Erik also

participated in the resupply missions for the French Army at Dien Bien

Phu, diving his C-82 Packet through heavy anti-aircraft fire from an

entry altitude of 4,000 feet to a drop altitude of 1,200 feet - leveling

off just above stalling speed - to make precision air drops on 45

missions.

Erik Shilling finally left America’s secret wars in Southeast Asia in 1966 - the only Tiger to fly in four wars - and returned to the United States to take a position with his old buddies in Flying Tiger Airlines. One of his jobs was interviewing new pilots, to determine if they had the “Tiger’s attitude.” He must have chosen well, when one considers that Flying Tiger Airlines was the primary organization involved in the American retreat from Southeast Asia in 1975, carrying orphans and other refugees in overloaded aircraft back to the United States.

When he passed away on March 18, 2002, aged 84, Erik Shilling - Flying Tiger and supreme aviator - had lived a life filled with episodes such as these. Never an ace, but recognized by his comrades in the AVG as their best pilot, he never held the spotlight. But for thirty years he lived at the controls of airplanes that inevitably seemed to find themselves in harm's way. Whether it was in a P-40 alone among the enemy, or a C-47 with a burning engine attempting to evade Japanese fighters with wild flying in the shadow of Mount Everest, or an unarmed C-54 on the deck in daylight deep within Communist China, Erik Shilling lived the quintessential aviator's life. Preparing to fight lung cancer with chemotherapy in March 2002 at age 84, he died peacefully in his sleep the night before he was to begin treatment - a Tiger to the end.

I was

privileged to meet Erik Shilling in 1977, when I flew in to photograph a

practice session of the Los Angeles Aerobatics Club in Delano, California

(he was their instructor), and parked my Bonanza next to a yellow Steen

Skybolt with the Flying Tiger insignia on its flank; I thought to myself

“That guy better  be

for real if he’s painted that on his airplane,” and was then introduced

to Erik - who was indeed “for real” - by the guy I had come down to

photograph. It was a kick to be one of the many “young guys” who spent

the next 25 years running to keep up with him. Trust me, it was an

effort.

be

for real if he’s painted that on his airplane,” and was then introduced

to Erik - who was indeed “for real” - by the guy I had come down to

photograph. It was a kick to be one of the many “young guys” who spent

the next 25 years running to keep up with him. Trust me, it was an

effort.

Among the many things Erik Shilling taught me was how to barrel roll that old Bonanza at a steady 1G, because “someday you’re going to be on final approach behind a jet airliner and find yourself suddenly upside down at 700 feet on final - this’ll save your life.” I never had to use that skill, but it was always good to know I could do it if I had to. It was even better to be able to list myself as a good friend of one of the finest flyers - and best people - America has ever produced.

|

THE KIT |

For a look at what’s in the box, check out the preview.

|

CONSTRUCTION |

To begin with,

when I made some critical comments about this kit at another modeling

forum recently, a well-known member of the

“we-can’t-criticize-them-or-they’ll-stop-making-kits-for-us” brigade

queried my knowledge about the early P-40 cockpit, asking the nonsensical

question, “When did you sit in a P-40?” Just to calm the brigade

members reading this

(since I am

going to be critical here), the answer is: “The last time I sat in an

early P-40 was September 25, 1998 - when were you in spitting

distance of one?” Now perhaps we can dispense with the ad hominem

baloney and get on to reviewing what’s there and what you can create with

that.

(since I am

going to be critical here), the answer is: “The last time I sat in an

early P-40 was September 25, 1998 - when were you in spitting

distance of one?” Now perhaps we can dispense with the ad hominem

baloney and get on to reviewing what’s there and what you can create with

that.

For me, construction started with the wing and tail sub-assemblies. Rather than provide the photo-etch hinges of previous releases, Trumpeter here provides plastic tabs on the separate control surfaces that allow the modeler to pose these in dynamic positions should they so desire, which is a vast improvement. I did not so desire, so I cut them off. I attached the upper aileron halves to the upper wing, gluing them from the inside, and repeated the process for the flaps and lower aileron halves. I then glued the wing upper halves to the lower piece and set this sub-assembly aside.

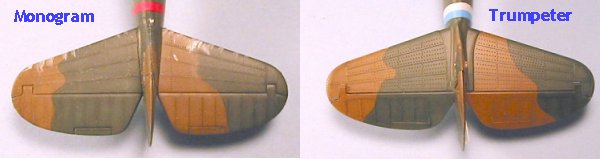

I assembled

the horizontal stabilizers and the elevators, and attached these in a

“drooped” position. The elevators are about 1 scale foot too narrow in

chord, with a wider-angle “bite” in their inner end. This results in a

strange look to the tail when these are assembled. I have compared the

tail of the Trumpeter with the accurate-shape tail surfaces of the

Monogram P-40B so the reader can see what the problem is here.

I assembled

the horizontal stabilizers and the elevators, and attached these in a

“drooped” position. The elevators are about 1 scale foot too narrow in

chord, with a wider-angle “bite” in their inner end. This results in a

strange look to the tail when these are assembled. I have compared the

tail of the Trumpeter with the accurate-shape tail surfaces of the

Monogram P-40B so the reader can see what the problem is here.

I looked at the engine, which is a model in itself, and decided not to build it, since I was not going to open the cowling inasmuch as Trumpeter only allows one to remove the upper cowling part, which doesn’t really reveal all the stuff in the engine compartment. This is too bad, because it wouldn’t have been that difficult to open it up further. My plan at the time was to blank off the opening for the exhausts and glue the exhaust stacks to that separately. In retrospect, I would now assemble enough of the engine to allow attachment of the exhaust stacks, and glue that in position inside the fuselage, since that is far easier than my “short cut” proved to be.

I attached the photo-etch screens at the ends of the radiator intakes, but these in the end were not that visible on the completed model.

Overall, the engine is over-built for what you can do with it - it’s my opinion Trumpeter could have taken the time and effort they invested here and put that into fixing the really substantial accuracy problems in the rest of the model, to good effect.

I next

turned to the cockpit assembly. This was when I discovered the Major

Glitch of the model: the cockpit is totally screwed up and completely

useless. It is only two-thirds as deep as it should be, which results in

a mis-shaped seat, instrument panel, rudder pedals, control stick,

cockpit side panels and all items found thereon. Making a scratchbuilt

cockpit in 1/32 with an acceptable level of detail for the scale was more

than I cared to do at the time, so my solution was to glue the canopy

closed; given that this model will ultimately be displayed in a glass

case where the viewer won’t get closer than two or three feet away, the

problem of the cockpit will not be apparent in that situation. For all

the rest of you, I suggest you set aside the model and await the release

of a resin cockpit by one of the aftermarket companies, since the model

looks truly terrible with the cockpit as provided if you want to open the

canopy.

I next

turned to the cockpit assembly. This was when I discovered the Major

Glitch of the model: the cockpit is totally screwed up and completely

useless. It is only two-thirds as deep as it should be, which results in

a mis-shaped seat, instrument panel, rudder pedals, control stick,

cockpit side panels and all items found thereon. Making a scratchbuilt

cockpit in 1/32 with an acceptable level of detail for the scale was more

than I cared to do at the time, so my solution was to glue the canopy

closed; given that this model will ultimately be displayed in a glass

case where the viewer won’t get closer than two or three feet away, the

problem of the cockpit will not be apparent in that situation. For all

the rest of you, I suggest you set aside the model and await the release

of a resin cockpit by one of the aftermarket companies, since the model

looks truly terrible with the cockpit as provided if you want to open the

canopy.

After gluing

in the “cockpit”, I glued the fuselage halves together and mated the

fuselage to the wing sub-assembly. Fit of these two sub-assemblies was

excellent and only required a little bit of Mr. Surfacer to close gaps.

I’ll note here that the hatch over the baggage compartment does not stand

proud of the fuselage side, as it does on this kit. I contemplated

sanding it down,

which would then have likely required rescribing not only the panel but

the surrounding countersunk rivet detail, and decided to let it pass.

sanding it down,

which would then have likely required rescribing not only the panel but

the surrounding countersunk rivet detail, and decided to let it pass.

When I went to assemble the cockpit canopy, I discovered that the rear windows are misshaped due to the fact that the fuselage is too circular in cross section there, where it should be close to a flat surface. Additionally, the side-view shape of the windows is wrong; I suspect this is so they can be made to fit the openings that result from the poor cross section shape of the rear fuselage in that area, since there would have to be an extreme curve of the window panel at the upper end to match the fuselage there. I am including two photographs taken of the P-40C restored by Fighter Rebuilders that will allow you to see what I mean. The bad cross-section shape can be lived with, but the resulting bad shape of the windows is very obvious to anyone who knows the early P-40.

Overall,

assembly of the kit was as easy as that of the MiG-3 kit. I only used

some Mr. Surfacer on the centerline seam of the fuselage and the leading

edges of the wings. Since this was to be a model of Erik Shilling’s

photo-recon airplane, I did not install the wing guns, since they were

removed on the original.

Overall,

assembly of the kit was as easy as that of the MiG-3 kit. I only used

some Mr. Surfacer on the centerline seam of the fuselage and the leading

edges of the wings. Since this was to be a model of Erik Shilling’s

photo-recon airplane, I did not install the wing guns, since they were

removed on the original.

I also constructed the “boots” for the wheel wells using aluminum foil. By the time most AVG P-40s saw combat, these had been removed since the wheel well was easier to clean without the canvas boot, which also rotted easily in the tropics given the kind of stuff picked up by the wheels and deposited in the boot. However, Erik’s airplane still had the boots at the time of his Bangkok mission.

|

COLORS AND MARKINGS |

Painting:

I painted the model in “US Equivalent Colors” of Dark Earth - for which I used Gunze Sangyo RAF Dark Earth with a little red added to get the U.S. color - and Medium Green FS34092 for the upper surfaces, and Tamiya Sky Grey for the lower surfaces. I used the camouflage patterns shown on the Cutting Edge decal sheets for the upper pattern. This was done at the factory with a hard edge. I achieved that by cutting out the masks from drafting tape, and then running thread 1/16" in from the edge of the mask, to raise the edge and get a smooth yet “hard” demarcation line. The colors were sun-faded, but not by as much as is seen in the color photos of AVG P-40s that were taken by Claire Booth Luce in March 1942 - again, this was because the model is of Erik Shilling’s airplane at the time of his famous mission, which was early on in the airplane’s career.

Once the

paint had dried, I gave the model a coat of Future and we were ready for

decals.

Once the

paint had dried, I gave the model a coat of Future and we were ready for

decals.

Decals:

I used the Cutting Edge decals which provide markings for Erik Shilling’s airplane. This airplane was originally in the Second Squadron, for which it had a blue fuselage stripe, before going to the Third Squadron, where it received a white ID stripe. While the shark’s mouth on this airplane is the most detailed of those Erik chalked on the group’s airplanes, it did not carry the Hells Angels insignia at the time of the Bangkok mission. Instead, it carried Erik’s personal insignia of a “Swami” (“Swami sees all, knows all,” as Erik explained it to me). These decals went down with no problems. I used the non-faded national insignia on both upper and lower surfaces of the wings, since these had not had time to fade that much at this point in the airplane’s career.

Unfortunately, none of the aftermarket sheets have any servicing stencil decals, and there are none on the Trumpeter sheet, which provides the prop blade specifications in black to go on a black surface, so they are therefore useless.

|

FINAL CONSTRUCTION |

After a final coat of Future, I gave the model several coats of thinned Dullcote. I didn’t want a dead-flat finish, inasmuch as this airplane had not had that much use and been that exposed to sunlight at this point in its career. For the same reason, I didn’t “ding” it much, since Erik told me the airplane was kept as clean as possible to improve performance. I finally attached the exhaust stacks and the corrected pitot tube made from Evergreen rod (since the one in the kit is incorrect for AVG P-40s).

|

CONCLUSIONS |

Trumpeter is

to me a very frustrating company, since their quality standards vary so

greatly from project to project that it is not possible to have a good

idea of what to expect from a new kit based on one’s experiences of the

previous kits. Every other plastic kit manufacturer manages to achieve

this sort of Minimum Standard, so I do not think it is an impossibility

to ask the same of Trumpeter. Where the MiG-3 was essentially accurate,

built out of the box, this kit is in real need of a corrected resin

cockpit and resin elevators to bring it to an acceptable display

standard.

Trumpeter is

to me a very frustrating company, since their quality standards vary so

greatly from project to project that it is not possible to have a good

idea of what to expect from a new kit based on one’s experiences of the

previous kits. Every other plastic kit manufacturer manages to achieve

this sort of Minimum Standard, so I do not think it is an impossibility

to ask the same of Trumpeter. Where the MiG-3 was essentially accurate,

built out of the box, this kit is in real need of a corrected resin

cockpit and resin elevators to bring it to an acceptable display

standard.

Trumpeter at this stage of their career reminds me of buying Chinese telephones five years ago - you could buy one and it would fall apart in two weeks, get a replacement that would last two months, and get a third that would last two years... and you couldn’t tell which was what from looking at it in the box. Hopefully Trumpeter will improve their quality control and their kit research the way the Chinese telecommunications equipment industry has improved their product in recent years.

I notice that

the branch of aircraft modeling that seems to have the largest percentage

of “thank-you-thank-you brigade members” among its ranks are the people

devoted to building these bigger models. Perhaps its due to the fact

that - until the release of the Tamiya Zero, and the Hasegawa Bf-109s and

Doras - they seemed lucky to have any models at all to build, let

alone anything

accurate, so that they have gotten into the habit of being happy with

whatever bones get thrown to them. My recommendation to these folks is,

“the squeaky wheel gets the grease.” Modelers do not have to accept crap

just because that’s what’s there. If the companies want to make money,

let them do it the old-fashioned way: create a product the customer

wants to buy - the Chinese need to read Deming on quality (as the

Japanese did 40 years ago) and learn that there’s more to capitalism than

producing 10,000 widgets a week; they need to be the right

widgets. All the other companies seem to be able to figure this out. It’s

obvious looking at this and other kits from Trumpeter that they can

achieve this minimum standard, and their Wildcat demonstrates they will

even go the extra mile to get things right. What they need to see is

that Doing It Right The First Time is no more expensive than screwing it

up.

alone anything

accurate, so that they have gotten into the habit of being happy with

whatever bones get thrown to them. My recommendation to these folks is,

“the squeaky wheel gets the grease.” Modelers do not have to accept crap

just because that’s what’s there. If the companies want to make money,

let them do it the old-fashioned way: create a product the customer

wants to buy - the Chinese need to read Deming on quality (as the

Japanese did 40 years ago) and learn that there’s more to capitalism than

producing 10,000 widgets a week; they need to be the right

widgets. All the other companies seem to be able to figure this out. It’s

obvious looking at this and other kits from Trumpeter that they can

achieve this minimum standard, and their Wildcat demonstrates they will

even go the extra mile to get things right. What they need to see is

that Doing It Right The First Time is no more expensive than screwing it

up.

So, for me, if the MiG-3 was a “9" on a scale of “10,” then this P-40B is a “7.5" on the same scale. It is the only kit of its sub-type in 1/32 scale, and outside of the atrocious cockpit and the incorrect elevators, the other accuracy glitches can be “lived with.” I really hope their coming 1/48 P-40B is not this kit pantographed down.

February 2004

Review Kit Courtesy of Stevens International

|

REFERENCES |

Interviews with Erik Shilling, February 6, 9, 12, and March 8, 2002.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and quickly by a site that has nearly 250,000 visitors a month, please contact me or see other details in the Note to Contributors.